Book review: Science vs. Religion: What Scientists Really Think by Elaine Howard Ecklund.

Book review: Science vs. Religion: What Scientists Really Think by Elaine Howard Ecklund.

Price: US$19.72; NZ$59.97

Hardcover: 240 pages

Publisher: Oxford University Press, USA (May 6, 2010)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0195392981

ISBN-13: 978-0195392982

This book reports on the recent Religion among Academic Scientists study in the US. A research project identifying the range of views on religion held by US scientists, and determining the statistical distribution of different beliefs among US scientists.

Elaine Howard Ecklund gives an overview of the research and the questionnaire it used. She also includes data from other studies. Data collection was funded primarily by the Templeton Foundation (the major grant was US$283,549) Participants were randomly selected from seven natural and social science disciplines at 21 US universities (I think the way such studies often neglect the non-university scientific institutions is rather short-sighted). The questions used related to religion, spirituality and ethics.

While the data and interviews of this study are interesting and useful I don’t think they necessarily support the author’s conclusions. I explain why below

Ecklund is a sociologist and currently the director of The Religion and Public Life Program at Rice University.

The “conflict paradigm” myth?

The book initially discusses the public perception of scientists and the science-religion conflict in the US and this gives an idea of Ecklund’s incoming agenda. She writes on the first page “The idea that religion and science are necessarily in conflict has been institutionalised by our nation’s elite universities.” She describes the desire for the independence of science from religion as “the conflict paradigm.” And justifies this by reference to (but no illustrating quotes from) White’s A History of the Warfare of Science With Theology in Christendom.

Many historians of science point out the relationship between science and religion has never been that simple. Nevertheless this “conflict paradigm” informs her view of the way the public think of science “. . many Americans see scientists as not only lacking faith, but as actively opposed to religion. This perception further sustains the conflict paradigm.”

This is an assumption and is a big problem with her approach. While she has obtained and presents data on the views of US scientists she provides nothing objective to justify her assumption about the views of the US public. Yet this assumption drives her analysis and recommendations.

Basically she concludes from her survey that “the general public misunderstand what scientists really think about the relationships between science and religion.” Something her data, which is not about the views of the public, doesn’t show. And her recommendation – this basically boils down to atheist scientists shutting up and religious scientists taking on all responsibility for the public face of science.

I can’t help asking if she had these conclusions, and recommendations, firmly in her mind before she collected any objective data. Has this influenced her interpretation of the data?

What do the US public think about scientists?

Mind you she does drop in a brief reference to data on public views in the very last section of the book. There she claims “nearly 25 percent of the American public think that scientists are hostile to religion.” So this was her basis for saying on page 2 that“. many Americans see scientists . . . as actively opposed to religion.”? Hardly an objective way of presenting statistical data.

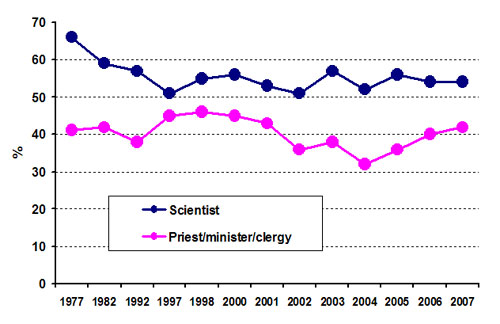

I have had a closer look at the source of her “nearly 25%” and wrote about it in Is atheism bad for science? This figure shows some of the relevant data from this source.

%age of US public considering professions of "very great prestige."

I really can’t see how it can have caused her concern that the public has an antagonist view of scientists.

Maybe public respect for the religious clergy declined after 2000, but not that for scientists.

What proportions of US scientists are religious?

While useful, the survey data and interviews are not really surprising. Religious beliefs among scientists are less common than among the public. Only 36% of scientists in this survey believed in a god compared with 94% of the US public. On the other hand 54% of scientists surveyed don’t “identify with a traditional religious tradition.” This latter figure was presumably obtained from the survey questions which asked “In what religion you were raised?” so “identification” may be an unwarranted presumption. Many adults do not identify with the past or present politics or religion of their parents.

That’s the problem with vague statistics like this. A Washington Post review interpreted this as “Fully half of these top scientists are religious”!. And even Ecklund’s summary later in the book could be misleading: “Nearly 50% of academic scientists have religious identity, and the majority are interested in spirituality.” As also a description of the book at her personal website: “It turns out that most of what we believe about the faith lives of scientists at elite universities is wrong. Nearly 50 percent of them are religious.”

I have commented before on her finding that no religious scientists claim their beliefs change in any way the methods they use in their scientific work (see Theistic science? No such thing). Just as we would expect.

On the other hand some of the interviewed religious scientists did claim their beliefs influenced their relationships with fellow scientists and especially students. They claimed it made them more caring and considerate. I can understand how that could be a personal perspective – but one that non-believers could also hold.

While interviews do help to illustrate attitudes revealed by the data, they are open to interpretation and misrepresentation.

Spirituality

Ecklund considers her data on “spirituality” of scientists significant. She concludes that many non-religious scientists are nevertheless “spiritual.” However, she admits to using the words “spirituality” and “religious” interchangeably in her questionnaire and interviews. So her discussion of this is frustrating. There is no guarantee that she recognises the same meaning of that word that the scientists actually interviewed did.

I think this confounds her conclusions. For example she appears to link “non-religious but spiritual” together with religious as a counter to the apparent large numbers of non- religious scientists. This misrepresents people who would describe themselves as atheist and spiritual, as I do. Personally, I think words like “spiritual” should be avoided, or defined in such surveys. For example there could have been clear questions related to specific spiritual pursuits like music, drama, etc.

The real conflict – epistemology

I personally believe that the “conflict paradigm” is another one of those myths actively promoted by religious apologists. Think about it. While many people do see a conflict between science and religion, and they know of historical and recent examples of conflict, how many actually believe “science and religion are necessarily and always in conflict?” Most people are aware that at least some scientists are religious and that this does not usually interfere with their science. And not all religious spokespeople are attacking science in the way that creationists do.

But I think most people are also aware that religion and science are not the same thing. They have different fields of interest. They have different methodologies. This was even formulated by Stephen Jay Gould into the concept of non-overlapping magisteria (NOMA). So no wonder science and religion have different conclusions. – and different uses.

However, these differences do point to an underlying inevitable conflict. Their different methodologies are based on different philosophies. Different epistemologies. In fact, it was not until science broke away from religion, obtained its independence and freedom to use a scientific methodology that a full scientific revolution could occur. Only then could science come out as the extremely effective way of knowing reality that it is now recognised for.

There is a science religion conflict! But it is not the conflict of the “conflict paradigm” myth. Scientists and religious believers are not inevitably and always in conflict with each other. Religious believers can do science – and scientists can have religious beliefs. However, this takes mental compartmentalisation (something humans are very good at) There is a conflict – it is epistemological.

Recommendations

Ecklund’s recommendations really mirror her apparent starting beliefs. She sees the public perception of scientists being hostile to religion as important (despite the lack of objective support for this). She also places a lot of importance on her perception that the US public is basically and dominantly religious and that therefore concludes the lower incidence of religious belief among US scientists interferes with the communication of science.

Her solution :

1: Atheist scientists should STFU. They should not be in the role of communicating science. Even when not commenting on religion well-known atheists can give science a “bad name.” Well that is her personal belief, made clear in the first few pages of her book where she says “Aggressive attacks on religion such as Richard Dawkin’s The God delusion do not accurately represent the complex way that scientists – even those who are not religious – actually engage religion and spirituality.” Well, of course not. No individual scientist’s writings do.

There is no evidence that the publication of The God Delusion has in any way turned the public away from science. But the common use of words like “aggressive,” “militant” and “strident” by opponents of Richard Dawkins are a bit of a give-away. Theistic opponents seem hell-bent on trying to shut up people like Dawkins completely, and not honestly debating them. And unsubstantiated claims like these are a rather obvious tactic.

2: Religious scientists should front for science communication. They are more acceptable to a religious public.

I am all in favour of religious scientists working as science communicators. I say go for it. We need more science communicators, religious or not. This already happens and they often do an excellent job. In the US Ken Miller, a Catholic scientist, has played an outstanding role in defending science against the attacks of creationists and fundamentalists

However, one does have to be careful when ideologically driven science communicators start to give more priority to their ideology than their advocacy of science. Unfortunately this happened with the initiative of Francis Collins when he set up the Biologos web site. It has now become a vehicle for advocating evangelical Christianity and not science. We also see this when scientific issues like cosmological “fine-tuning” are used by believing scientists to justify god beliefs.

I believe that when ideological views confuse scientific issues in this way science is no longer being communicated.

Conclusion

The data and interviews reported in this book, and other publications from the survey, will obviously be useful. Even if the results really just confirm other surveys. However, my advice is to take the conclusions and recommendations with more than a grain of salt.

Scientists are no more hostile to religion than they are to magic.

Plenty of scientists out there accept magic as part of their daily lives that allow them to feel enriched and forfilled. Magic has never been in conflict with science. In fact, without magic, it’s difficult to even concieve of modern day science.

Some disbelievers of magic tend to, sadly, trivialise and insult magic by making crude caricatures of it and talking about rabbits and hats and sawing ladies in half. They conveniently forget the deeper meaning of magic such as doing the ol’ water/wine switcheroo at parties, throwing sticks on the ground and having them turn into snakes with the stronger snake then eating the weaker, simple curses that produce bears that then rend children limb from limb, the utterance of a magic word that create all matter itself and of course magic dust that turns into people etc, etc, etc.

LikeLike

Don’t forget the talking donkey trick or the running of demented pigs over cliffs, Cedric.

Yes Ken, spiritual is a vague term. For as long as I can remember I’ve felt my eyes glazing over, my attention wandering and my ears no longer hearing as soon as conversation moves to matters spiritual or descriptions of persons or their nature as being spiritual.

For some unfathomable reason many regard being spiritual or having a spiritual nature as being worthy of kudos.

Spirit = ghost. Why should embracing and nurturing the concept of ghosts and all things ghostly be worthy of kudos?

LikeLike

…spiritual is a vague term.

Ah such arrogance.

Many, many prominent philosophers would beg to differ. Clearly, you have not spend decades studying the real issues.

Spirit is not something so easily dismissed. Without spirit, there would be no essense. Without essence, there would be no duality. Without duality there would be no inner being. Without inner being, there can be no peace.

Clearly, however, peace is a concept that even your narrow, poisoned, hate-filled and naive, militant atheist worldview must admit to. Therefore, the spirit exists.

Further more, I object to your ad hominem rants and I dispair that Ken will offer me an apology.

LikeLike

Without essence, there would be no duality.

You’re sailing close to the wind, or should I say, close to a pile of flaming faggots.

It’s a trinity not a duality you heretic.

LikeLike

(giggle)

LikeLike

Pingback: Gnu bashing once again | Open Parachute

Despite its detractors, and the ongoing tension at the intersection between science and religion, I do think Stephen Jay Gould’s “NOMA” concept has merit. I do not think there is any underlying epistemological conflict between science and religion. But there is conflict when either tries to control the other, and when either tries to deny the reality of the other’s domain or make pronouncements about its nature.

Science had to be freed from religion because it is not religion’s business to determine or make statements about the way material reality operates within its own domain.

By the same token, science has no business determining or making statements about spiritual reality and how it operates within its own domain. Any individual or group that wants to is free to deny the reality of spirit and of God. But those are not scientific statements. Science doesn’t deal with spiritual reality and God. It can therefore make no determination about their existence or non-existence. The most science itself can be is agnostic.

What science can do is correct religious people when they make pronouncements about the nature of the material universe based on religious beliefs. That’s not the role of religion. As long as religion tries to cross the border into the domain of science, religion will continue to lose because it’s venturing into territory that religion is not designed to deal with.

I have no problem with people being atheists if they so choose. However, I find the antitheistic arguments of the new atheists to be weak and superficial. They attempt to use science to deal with a realm that science is not designed to deal with. The new atheists also tend to uncritically accept fundamentalist religion as the essence of religion and theism. Most of their attacks on religion are therefore aimed at a rather weak straw man.

Fundamentalism is a rather recent development in the history of religion. It arose only in the 1800s. And it arose, not out of the underlying nature of religion and spirituality, but as a reaction to the rise of science itself, among certain religious people and groups that do not understand the distinction between spiritual and material reality.

Ironically, fundamentalists tend to have a very materialistic view of reality. For example, they commonly believe in a bodily resurrection and a future physical existence in the material universe rather than a resurrection in a spiritual body inhabiting a distinct (non-physical) spiritual realm. The materialistic nature of the religion of fundamentalists explains why they are the ones battling it out with science and with atheists. They’re trying to occupy a “magisterium” (to use Gould’s word) that is not the proper realm or study of religion.

LikeLike