This post is the last in a series on human morality (see, Objective or subjective laws and lawgivers, Subjective morality – not what it seems? and Drifting moral values). These are not meant as an academic treatment of the subject (as one commenter (OS) seemed to think). As I said in my first post, I am responding to ideas presented by Zach Weinersmith and Sean Carroll about subjective and objective morality on their blogs (see Pankration Ethics and Morality and Basketball) and taking the opportunity to clarify my own ideas about physical laws and moral laws. That’s what blogs are for aren’t they?

So I welcome comments and genuine criticisms.

The camera metaphor for human morality describes an “auto mode” were we react unconsciously to situation and make our moral judgements and decisions without rational consideration (see Subjective morality – not what it seems?). We may attempt to explain later the reasoning behind those decisions, but psychologists like Jonathan Haidt point out these are actually rationalisations, not description of actual reasons. While this is the mode we use most of the time, there is also the “manual mode” — where we do attempt to reason through moral situations (see Drifting moral values). We may be rehearsing our rationalisations. But we also may be participating in public discussion. The current discussion on the marriage equality bill is an example.

The camera metaphor for human morality describes an “auto mode” were we react unconsciously to situation and make our moral judgements and decisions without rational consideration (see Subjective morality – not what it seems?). We may attempt to explain later the reasoning behind those decisions, but psychologists like Jonathan Haidt point out these are actually rationalisations, not description of actual reasons. While this is the mode we use most of the time, there is also the “manual mode” — where we do attempt to reason through moral situations (see Drifting moral values). We may be rehearsing our rationalisations. But we also may be participating in public discussion. The current discussion on the marriage equality bill is an example.

But these two modes are not mechanically separated as in a camera. It’s not a matter of flipping a switch or making a choice of modes. And as I said before even when someone is consciously reasoning they are still influenced by their unconscious feelings and emotions. But I think it’s also important to realise our “auto” moral mode is not static. It is over time influenced by what goes on in our conscious mind (the activity of our “manual” moral mode) – and in our surrounding environment.

Learning

The normal learning process usually involves a transfer of consciously rehearsed reasoning or action into our subconscious. What we initially learn to do consciously, and therefore requires concentration and mental effort, eventually becomes embedded in our subconscious and we do it without thinking. Consider how you learned to ride a bike or drive a car and how this eventually became an unconscious skill.

The normal learning process usually involves a transfer of consciously rehearsed reasoning or action into our subconscious. What we initially learn to do consciously, and therefore requires concentration and mental effort, eventually becomes embedded in our subconscious and we do it without thinking. Consider how you learned to ride a bike or drive a car and how this eventually became an unconscious skill.

Cordelia Fine describes how during the learning process our conscious mind eventually delegates responsibility to our unconscious mind in her book A Mind of Its Own: How Your Brain Distorts and Deceives .

.

“Everyday activities like walking and driving perfectly illustrate the importance of being able to delegate responsibility to the unconscious mind. This point was vividly brought home to me as I observed my small son learning how to walk. When he was twelve months old it was an activity requiring the utmost concentration. No other business—receiving a proffered toy, taking a sip of water, even surveying the pathway ahead for obstacles—could be conducted at the same time. Imagine if this carried on throughout life, with passersby on the street plopping clumsily to their bottoms should you distract them for an instant by asking for directions. But fortunately, the unconscious gradually takes over. The previously tricky aspects of walking—balancing upright, moving forward, the whole left-foot-right-foot routine— become automatic and mentally effortless. And once a skill moves into the domain of the unconscious mind, we free up conscious thought for other matters. The learning driver is a poor conversationalist because his conscious mind is fully taken up with the complexities of steering, changing gears, and indicating. As driving becomes automatic, we can offer something a little more fulfilling to our front seat companion than a series of fractured mutterings and muffled cries of “Sorry!” Precious conscious thought becomes available again.”

Just imagine if every skill your “learned” had to be performed consciously. We just could not operate that way, and its the same with our day-to-day social interactions and moral judgements. We just could not have survived as a species if all that we learned required deliberate engagement of the conscious process every time we used it. We wouldn’t just be “plopping clumsily on bottoms” when distracted while we were walking. We just wouldn’t react quickly enough to life threatening situations. And we would find life in a society of people impossible.

So I think that our conscious deliberation on moral issues, as might occur when we are taught by parents or other adults, or when we take part in discussions and decisions, does make changes in our subconscious mind. The exercise of our “manual mode” then leads to changes in our “auto mode.” For example, learning about, or discussing, the consciousness of other animals, their ability to feel pain and emotions, may eventually lead to someone who was originally a meat eater to automatically feel repelled by meat dishes.

Mind you, teaching by an adult does not necessarily lead to an “auto” moral mode which produces the right result from the perspective of a modern humane person. Consider, for example, the sort of learning that goes on in families belonging to inhumane religious sects. Many children from these families grow up to automatically associate strong women, racial minorities or homosexuals with a feeling of disgust.

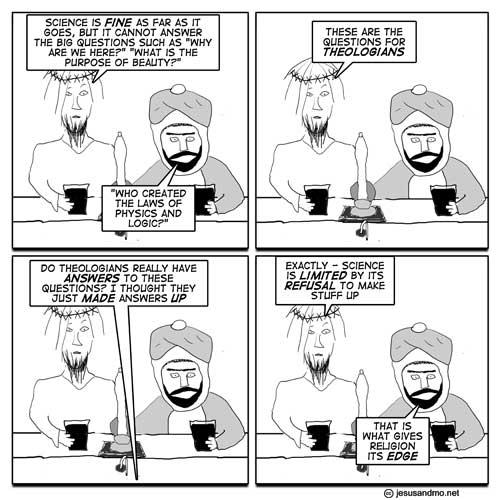

Even mainline Christian denominations and sects tend to continually argue for the status quo or return to previous moral norms. They seem to particularly react against political and social pressure to update laws and moral codes on the basis of reasoned and collective discussion and evidence. This results in such organisations continually being seen as backward and conservative.

Cultural learning

A tremendous amount of our learning occurs involuntarily, and not in formal lessons, lectures and sermons. For many adults this may be the only way we continue to learn. We may not be aware of it, but we are continually learning while being entertained. And I don’t mean via advertisements – more through “product placement.”

Entertainment it’s a relatively painless way of learning. Of course, as many people comment, we may be learning a load of rubbish. Not just about foods and fashions, but also about social attitudes – which eventually end up influencing our “auto” moral mode.

But, because our entertainment reflects features of our society it also often reflects good changes in our society. Or at least helps to make acceptable things and people we may have otherwise had negative feelings about. Today it is relatively common to see homosexuals and homosexual relationships presented in a positive way in TV drama, films and soap operas. Similarly we have developed a more accepting attitude towards single parent families, to women working. Even to strong professional women because we have become used to seeing them day-to-day in these dramas and soap operas.

Positive presentation in fictional drama also enables positive presentation in real life. Homosexuals have been “coming out” – we all become aware that our friends and acquaintances may be homosexual. These a real people and this breaks down those old negative associations we may have previously learned. In recent years a similar thing has happened with atheists, especially in the USA. The word is losing its negative connotations.

TV may be particularly effect in this cultural learning but it is a relatively new phenomena. I think literature and art have also provided an important medium for cultural learning over the years, and well before modern methods of communication. Many timeless moral situations and dilemmas, as well as topical issues, have been covered by literature and drama. Possibly one of the most important things parents can do to ensure the moral education of their children is to encourage reading, and allow access to a variety of genre.

Swings and roundabouts

I have conceded that cultural layering may be promoting some acceptance of rubbish as well as negative moral attitudes. That’s an inevitable downside. But as long as there are some people in society who engage their “manual” moral mode and take part in society-wide discussion of topical moral issues there is scope for the passive cultural learning by the rest of society. I have argued that there is an objective basis for human moral values in human nature. The fact that we are a sentient, intelligent, social and empathetic species. These discussions offer an arena for the objectively based human moral values to exert their influence. In effect it is the manual moral mode of society’s leaders and thinkers, of our writers, artists and actors, who have enabled a reasoned consideration based on positive moral value to influence the “auto” moral mode of the rest of society.

Similar articles

-37.798130

175.315066

Here’s a fascinating talk on the science of consciousness given at the TED talks in CERN.*

Here’s a fascinating talk on the science of consciousness given at the TED talks in CERN.* and Mind, Language And Society: Philosophy In The Real World

among others.